edinburgh, scotland

—

As “Auld Lang Syne” circles the world every New Year’s Eve, with men and women of all ages singing along in unison, Edinburgh’s Poet Laureate Michael Pedersen says the song’s enduring power lies not only in its tradition, but in its mysterious power to bring people together.

Pedersen, an award-winning Scottish poet and author who is currently writer-in-residence at the University of Edinburgh and the city’s Poet Laureate Makar, told CNN that the song’s customary performance late at night on December 31 was never formalized, but simply felt right.

“For generations, this song has been sung because it’s perfect for the new year,” he says. “There’s nothing in this song that tells you that you have to sing this song at that moment. People just had an emotional compass for this song. They gathered outside City Hall and sang it. And it drifted into place in the new year, like a glacier of great and beautiful songs.”

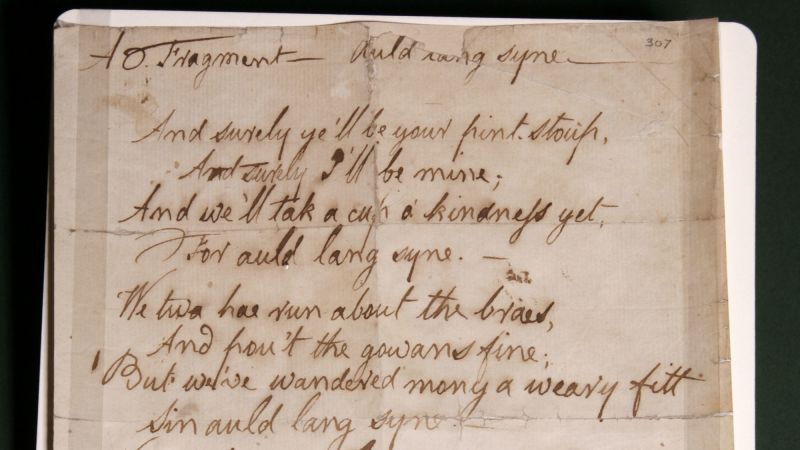

Despite its popularity, few people claim to know all the lyrics to the song, which was first written by Robert Burns in 1788. But that did little to detract from the song’s appeal.

The phrase “auld lang syne” roughly translates to “of olden times,” but Pedersen said the modern equivalent would be “for old times.” He said that the core of the song is “a story that looks back at childhood friendships that were rekindled through handshakes and friendly drinks.”

“This is a song of reunion, not farewell,” he added. “It’s about celebrating the happy days gone by and the glorious bonfire that shines in our bellies when we’re back together.”

As a Scot, watching the song circle the globe each year feels like “sending the Scottish bat signal,” Pedersen said.

“Auld Lang Syne was truly Scottish, but Scotland has become the ultimate cosmopolitan citizen,” he said. “Everyone made it their own. What a beautiful expression of art and humanity, to write something national and deeply personal, and to have your life projected onto it.”

Part of that staying power, he argues, is physical. This song isn’t just sung, it’s performed.

“It happens at very beautiful moments, like the end of the year, weddings, large gatherings,” he said. “We hold hands, form a circle, and physically express our friendship. Most of us hum the verses and sing emphatically during the chorus. And it brings us all together. It’s a comforting, song-sized hug that has survived for centuries.”

When it comes to choreography, Pedersen says the arm-in-arms moment is slower than many people think.

“Traditionally, the first five verses are hands clasped,” he said. “And on the fifth day, everyone will be walking in and out of the circle with their arms crossed and holding the hands of their neighbors. Of course, there will be criminals and thugs running in in different places. That’s part of the beauty and part of the misery.”

The question of authorship remains one of Scottish literature’s most enduring debates. Robert Burns claimed that he only wrote down the version he heard at the coaching inn and later arranged it to fit the song.

“There’s no evidence of how well he adapted,” Pedersen said. “It could have been a word or two, or a major rewrite by Burns.”

Burns’ publisher, George Thomson, changed the music again after Burns’ death, creating the melody we know today.

“To this day, critics argue whether Burns led us in the wrong direction, but it was his fault all along,” Pedersen said.

“He was known to avoid attributing parts of his work, sometimes because it was too heretical, and sometimes because he wanted to see how people would react without the backdrop of his fame. This work remains a beautiful and enjoyable mystery.”

Mr Pedersen said he was now adding his own contribution to Scotland’s New Year celebrations with a poem called “Boys Holding Hands”, inspired by Mr Burns and written out of a dedication to their lifelong friendship.

“I’ve always worshiped at the altar of friendship,” he said. “Inspired by Burns, I wanted to write my own poem about holding hands to celebrate friendship. ‘Boys Holding Hands’ is that piece. It’s about holding hands with your friends to celebrate all the time you’ve had and all the time you’ll have in the future.”

He said the poem is also a gentle challenge to the emotional constraints placed on men.

“There’s a real bravado about masculinity that causes us to keep so many of our emotions in our bellies and let them melt like streaks until we have no voice,” he says. “We have to pour out all that dirty, extravagant sentimentality to make ourselves better, more equipped, more loving people.”