Iran appears to be ramping up its rebuilding of its ballistic missile program, despite last month reintroducing UN sanctions banning arms sales and ballistic missile activity to the country.

European sources said that since the so-called “snapback” mechanism was activated at the end of September, several ships of sodium perchlorate, the main precursor for producing solid propellants that power Iran’s medium-range conventional missiles, have arrived from China at Iran’s Bandar Abbas port.

The sources said the shipment, which began arriving on September 29, contains 2,000 tons of sodium perchlorate, which Iran purchased from a Chinese supplier following a 12-day conflict with Israel in June. The purchase is believed to be part of a determined effort to rebuild the Islamic Republic’s depleted missile inventory. Some of the cargo ships and Chinese companies involved have been sanctioned by the United States.

The handover came after more than a decade-old U.N. sanctions were reinstated by the snapback mechanism, a provision for Iran’s violations of the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) agreement to monitor Iran’s nuclear program.

Under sanctions reimposed on Tehran last month, Iran is not supposed to carry out any activities related to ballistic missiles capable of delivering nuclear weapons. U.N. member states also need to block supplies to Iran that could help it develop nuclear weapons delivery systems, which experts say could include ballistic missiles.

Countries are also required to block arms production aid to Iran. China, along with Russia, opposed the reimposition of sanctions, saying it would undermine efforts toward a “diplomatic solution to the Iranian nuclear issue.”

The transported substance, sodium perchlorate, is not specifically named in the United Nations document on substances prohibited for export to Iran, but is a direct precursor to ammonium perchlorate, a listed and prohibited oxidizing agent used in ballistic missiles. But experts say the sanctions’ failure to explicitly ban the chemical could leave room for China to argue it is not violating any UN bans.

CNN used ship tracking data and crew social media to track the journey of multiple cargo ships that sources identified as being involved in a recent shipment of sodium perchlorate from a Chinese port to Iran. Many of these vessels are believed to have made several round trips between China and Iran since the end of April. Officials said the crew appeared to be employed by a shipping company in the Islamic Republic of Iran, and their regular social media posts documented their stops on their journey from China to Iran.

Among them was the MV Basht, which was already subject to U.S. sanctions, leaving China’s Zhuhai port on September 15, arriving in Bandar Abbas on September 29, and then returning to China.

Following a similar route, Barjin departed from Gaolan on 2 October, arrived at Bandar Abbas on 16 October, and departed again for China on 21 October.

According to Western intelligence, the Eliana left China’s Yangtze Port on September 18 and arrived in Bandar Abbas on October 12. Finally, the MV Artavand left China’s Liuheng port and arrived in Bandar Abbas on October 12, with its AIS tracking system deliberately turned off to hide its movements.

It is unclear whether the Chinese government is aware of the shipment. In response to CNN’s questions about the transaction, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson said that although he was “not familiar with the specific situation,” China “consistently enforces dual-military goods export controls in accordance with its international obligations and domestic laws and regulations.”

“We would like to emphasize that China is committed to resolving the Iranian nuclear issue peacefully through political and diplomatic means and opposes sanctions and pressure,” the spokesperson continued, adding that Beijing views the reinstatement of sanctions under the snapback mechanism as “unconstructive” and a “serious setback” in efforts to “resolve the Iranian nuclear issue.”

Similar shipments have been reported before, but the escalation signals a new eagerness to arm the Islamic Republic since the 12-day war in which the Israeli military targeted at least a third of Iran’s medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) surface-to-surface launchers.

“Iran now needs more sodium perchlorate to replace missiles consumed in the war and to increase production,” said Jeffrey Lewis, director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Project at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies.

He told CNN that the best way to think about this right now is to suspend hostilities as both sides seek to rearm.

“2,000 tons of sodium perchlorate is enough for about 500 missiles. That’s a lot, but Iran planned to produce about 200 missiles a month before the war, and now it has to replace all the missiles that Israel destroyed or used.”

long-standing bond

China has long been a diplomatic and economic ally of sanctions-hit Iran, decrying “unilateral” sanctions against the country by the United States and buying up much of Iran’s oil exports, despite not reporting any purchases in years.

Its energy trade relies on a network of ships that filter Iranian crude to independent refineries on China’s coast, often through intermediary countries, a practice that separates refining from Chinese state-owned companies that are vulnerable to U.S. sanctions, analysts said. These so-called teapot refineries are known to work with what are often referred to as shadow tanker fleets that use covert tactics to smuggle sanctioned goods.

European security officials believe a similarly opaque system involving front companies with little more than fake numbers and billing addresses is being used to keep sodium perchlorate flowing into Iran. So do more legitimate companies, including two that were already sanctioned by the US in April for their involvement in a “network that procured ballistic missile propellant raw materials on behalf of the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC).” Most of the companies involved are based in Dalian, a port city in northeastern China, according to sources.

In February, CNN reported that 1,000 tons of sodium perchlorate had been shipped from China to Iran. By April, the United States had imposed sanctions on multiple entities in Iran and China, including vessels believed to play a role in “a network to procure ballistic missile propellant raw materials on behalf of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC).”

Still, the shipments continued, with the Revolutionary Guards’ Self-Sufficiency Jihad acquiring another 1,000 tons of sodium perchlorate, which left China’s Taicang on the Hamouna on May 22, arriving in Bandar Abbas on June 14 or 15, sources said. The ship set sail for an Iranian port on April 27, less than a month after a massive explosion apparently caused by sodium perchlorate killed 70 people. Hundreds were injured.

The latest shipment represents a much larger shipment in a shorter period of time. The first of 10 to 12 convoys being tracked by European intelligence sources arrived in Iran on September 29, two days after the snapback mechanism triggered in August by the JCPOA’s European partners Germany, France and Britain reinstated UN sanctions. All the others left China after sanctions were imposed.

Tong Zhao, a senior fellow in the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said China’s position on the legal status of reimposing sanctions could be related to how authorities view such shipments.

“First and foremost, China, along with Russia and Iran, condemned the legality of the snapback in a joint letter to the United Nations on October 18, indicating that Beijing likely does not believe it will be bound by the re-imposed measures,” Zhao said.

If a snapback is not triggered, October 18 would be the official end date for the 10-year JCPOA, at which point the option to reimpose past UN sanctions and restrictions on Iran’s nuclear program would expire and the Security Council would close Iran’s nuclear file.

Indeed, China joined forces with Russia in September to seek a six-month extension of the JCPOA, arguing that more time is needed for diplomatic efforts and pointing to what Beijing sees as a sign that Iran wants to work with the international community on regulating its nuclear program. The UN Security Council rejected a Chinese-backed resolution in September, the day before the snapback took effect.

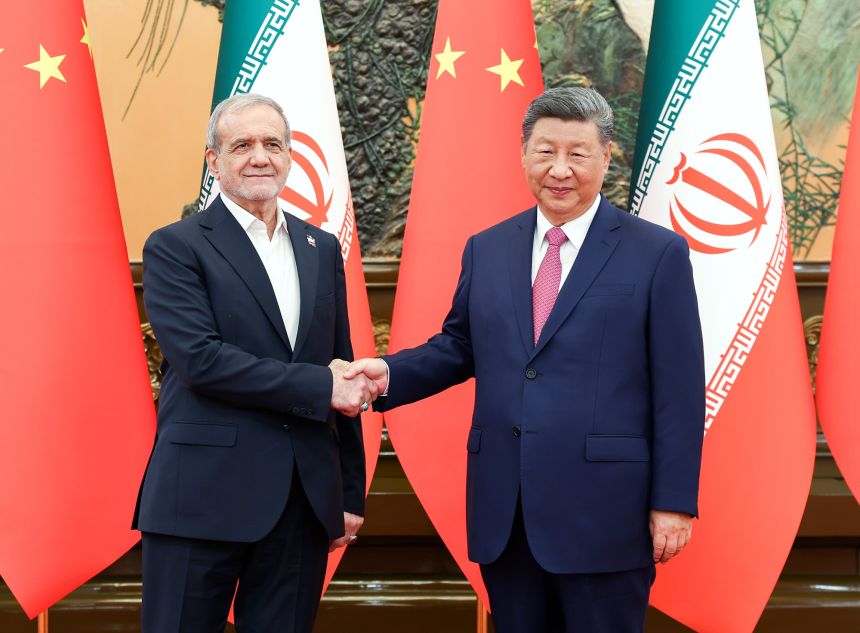

The Chinese government was one of six countries to sign the JCPOA with Iran in 2015, along with France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States. At a meeting between Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian in September, Xi “valued Iran’s repeated pledge not to seek the development of nuclear weapons” and reiterated China’s position that it “respects Iran’s right to peaceful uses of nuclear energy.”

Mr. Zhao also pointed to the fact that the export of sodium perchlorate was not explicitly prohibited under the pre-JCPOA sanctions regime, which is now being re-enacted. He added that the revived U.N. resolution prohibits member states from providing Tehran with “goods, materials, equipment, objects, or technology” that could contribute to Iran’s development of nuclear weapons delivery systems.

So although sodium perchlorate is not mentioned by name, “it should be subject to broad catch-all regulations for materials used in solid-fuel missile construction,” he said, although the fact that it is not explicitly banned could leave a lot of room for interpretation by China and other countries.

“The Chinese government may be aware that these exports indirectly support Iran’s missile program,” Zhao said, “but China may also see this as a matter of principle, asserting China’s sovereign right to make independent export control decisions on items not explicitly prohibited by the United Nations.”

CNN’s Simone McCarthy contributed to this report.