Bertha Zúñiga is not used to the threat. She remembers a day several years ago when she and her colleagues were chased by a machete-wielding attacker in western Honduras.

The vehicle blocked the car, and the passenger stepped out with weapons and tried to attack the group. They managed to escape, but the incident was not the first. It was also not the last time Zuniga faced a violent threat.

The encounter comes more than a year after Zuniga’s mother, Berta Caceres, a prominent Honduras Indigenous rights activist, was killed in her home in March 2016, and Zuniga took away the civil council of her group, the Honduras (Copin) general and indigenous organizations, and Zuniga was killed in her home.

Zuniga was when her mother started the group to protect Indigenous Lenka lands from the commercial interests of community harming and misusing it.

Zúñiga’s group is fighting controversial projects, such as the rich Agua Zarka Dam in northwestern Honduras, where activists will make a living for the Lenka people. Communities fear that the Gualcalc River hydroelectric power plants will destroy the unique ecosystem and the community’s agricultural production areas and sources of food and natural medicine. However, Caceres’ move towards the project faced a strong pushback.

Global witnesses from the Environmental and Human Rights Research Group said in 2023 Honduras was the third most deadly tied to Colombia and Mexico behind Brazil, and had the world’s best killing of per capita environmental defenders.

In April 2013, Caceres organized a road blockade in the Rio Blanco area and stopped Desarrollososener Géticos Sociedad Anónima (DESA), the utility company that owns and operates the Agua Zarca Project. Despite attempts to eviction and violent attacks, the lockdown lasted for more than a year.

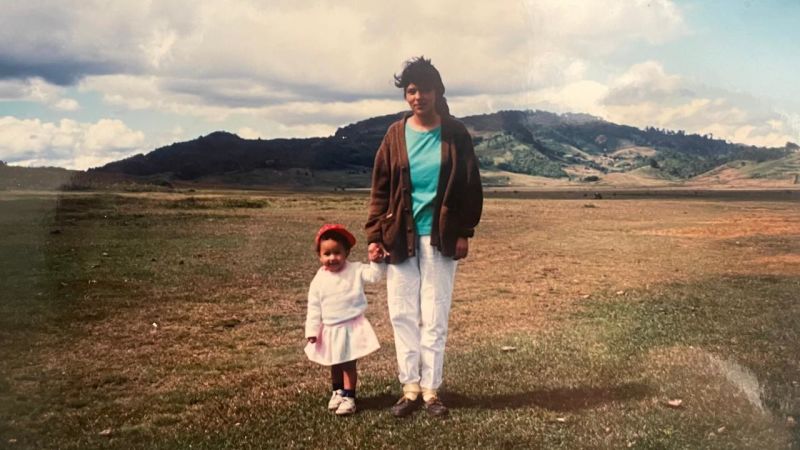

“We’ve started to see it as a much more aggressive fight in Copin history than ever,” Zuniga told CNN. “My mother always took me into the community. I saw what was going on and learned first hand there, but she held back a lot. She didn’t want to let me go to Rio Blanco.”

When Zuniga insisted on going to the area, her mother instructed her to use her middle name and not to reveal who she is.

Caceres knew that her job was dangerous, so from an early age, Zuniga learned to take her safety seriously in the fear of the temptation. Even after she was old, someone had to take her to school and pick her up. She had no freedom that most of the other children had.

The year before her murder, Caceres sat down with adult children to speak. “She said something could happen in this country and we shouldn’t be afraid,” Zuniga said.

A team of international legal experts investigating Caceres’ murder determined it was the result of a larger plot, not an isolated incident. To date, eight people have been declared in connection with her death, including a former senior employee of Desa. The company was unable to contact us for comment, but previously maintained the employee’s innocence and had long denied its connection to the murder. Famous convictions included former executive Roberto David Castillo Mezia, who was sentenced to more than 22 years, and former environment manager Sergio Rodriguez, who was sentenced to 30 years. Both claimed that they were innocent.

Most of Honduras’ water resources are located in Indigenous territory, and governments often allow business groups access to these resources without proper consultation with local Indigenous communities. Laura Frons, a senior adviser to Global Witness, often aims to quickly extract natural resources in a way that maximizes economic benefits without considering the impact on the environment or local people.

“These local populations usually benefit little or none,” she told CNN.

Over the years, after the 1998 coup was devastated by events like the 1998 coup that drove Jose Manuel Zelaya, government policies that support the private sector and businesses aimed at profiting from the country’s natural resources have boosted the economy.

A few days after Caceres’ death, Copin member Nelson Garcia was fatally shot. In January 2023, it was discovered that Aly Magdaleno Domínguez Ramos and outspoken activist Jairo Bonilla Ayala against iron ore mines had died in northern Honduras. And last year, Juan Lopez, who protested mining and hydroelectric projects, was shot dead on his way home from church.

Before her death, Caceres himself had a shot fired into the air as a warning, shooting her car with a stone, Zuniga recalls.

Sensitive information about the security details that the Honduras government gave to Zuniga’s family after the death of his mother was leaked earlier this year shows that her family is still at risk, almost a decade after the prominent murder of her mother.

Screenshots of the document are spread across social media, with details such as make, model, plate number, vehicle identification number, and more identifying the number of vehicles in the car that grandmother travels and is registered.

The Honduras Special Prosecutor’s Office acknowledged that the leak was a “very serious” violation of confidentiality and that CNN had informed that an investigation into the leak was underway and that the protection measures for Zuniga and her family must be adapted and strengthened.

“It’s not easy to feel like a target for an attack,” Zuniga says. “It’s not that I’ve never lived before, but of course I’m a little worried about what that means,” she says of the leak.

A few days before the information leaked, photos of Zuniga’s face bruised and blood stained circulated to social media. It reminds me of the time when Zuniga said that Copin had spread emotional images of his mother on social media, known as the Smear Campaign, which aimed to reduce the group’s work.

However, Zúñiga is not deterred. She is responsible for the battle for her rights to the Indigenous lands, greater than herself and her family, and she sees her mother still feeling that she is helping her.

“Her spirit comes with me and protects me,” Zuniga says. “I know she’s with me.”