For visitors, Venice is a glorious tapestry of historic buildings, waterways, bell towers and red roofs, engraved on structures around the city with powerful winged lions, a symbol of the Republic of Venice.

Perhaps the most famous lion is a bronze statue standing on the pillar of Piazsetta, adjacent to St. Mark’s Square. And now, researchers believe that the statue was made in China.

After studying metal lion samples using lead isotope analysis, researchers from the University of Padua, Northern Italy, discovered that copper is used to create bronze alloys (a mixture of copper and tin) in the original bronze factory, according to a study published in ancient times in the journal Thursday.

This would explain why the heights of 4 meters – (13 feet) and 2.2 meters (7 feet) that were thought to have been made locally in Syria or Anatolia, are stylistically mystical.

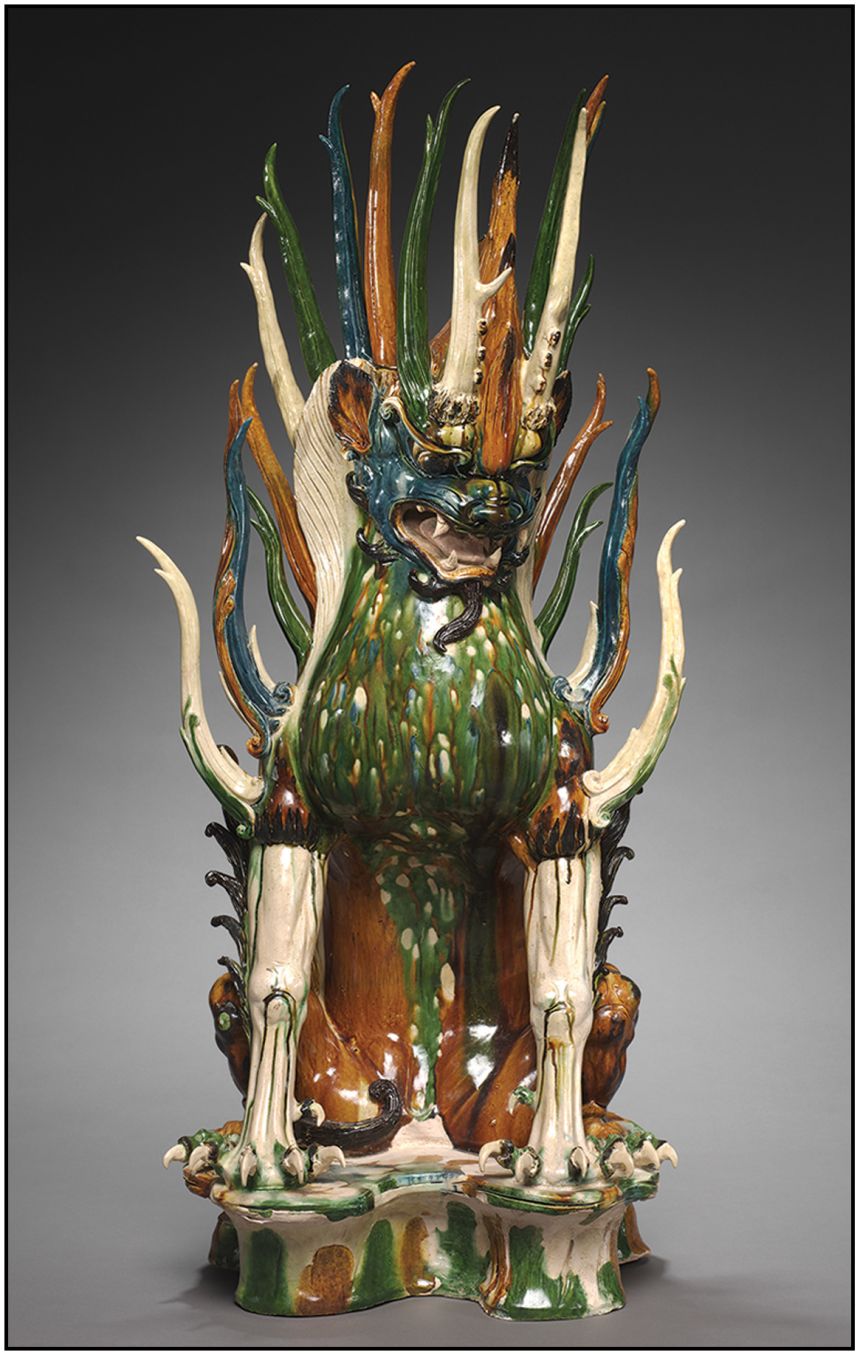

Although set up in St. Mark’s Square in the 13th century, the lion is closer to that of the Chinese production (618-907) during the Tang Dynasty found in medieval Mediterranean Europe, researchers argue by citing the shape of the nose and scar from previous horn removal.

The column in which the lion stands is from Anatolia (part of modern turkeys), and the lion itself has been repaired several times, with the earliest recorded instance in 1293.

“It is possible that Marco Polo’s father and uncle were in charge of acquiring the sculpture during the four years he spent in the courtroom of Kubrai Khan during his first trip,” the researchers added that the visit likely took place between 1264 and 1268.

The animal was originally Zhènmùshòu, the guardian of the monumental, fierce, lion-like tombs of the Tang Dynasty, the author speculates.

After Porus visited the Mongol courthouse, he sent the statue back to Italy and was “resurrected with caution and labor” to make it look like the sacred coat of arms of Saint Mark, they added.

“If the written information is inexplicable, the intentions and logistics behind the journey to Venice remain open to elusive interpretations. If the installation of the ‘lion’ was intended to send a powerful, defensive political message, we can now read as a symbol of an impressive connection in the medieval world,” they added.