Philadelphia (AP) – Archaeologist studying ancient civilizations in the north Iraq In the 1930s, we became friends with close friends. Yazidi CommunityDocumenting daily life in later rediscovered photos Islamic nation Extremist groups devastated small religious minorities.

The black and white images were scattered across around 2,000 photos. Excavation Stayed at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, which led to ambitious excavations.

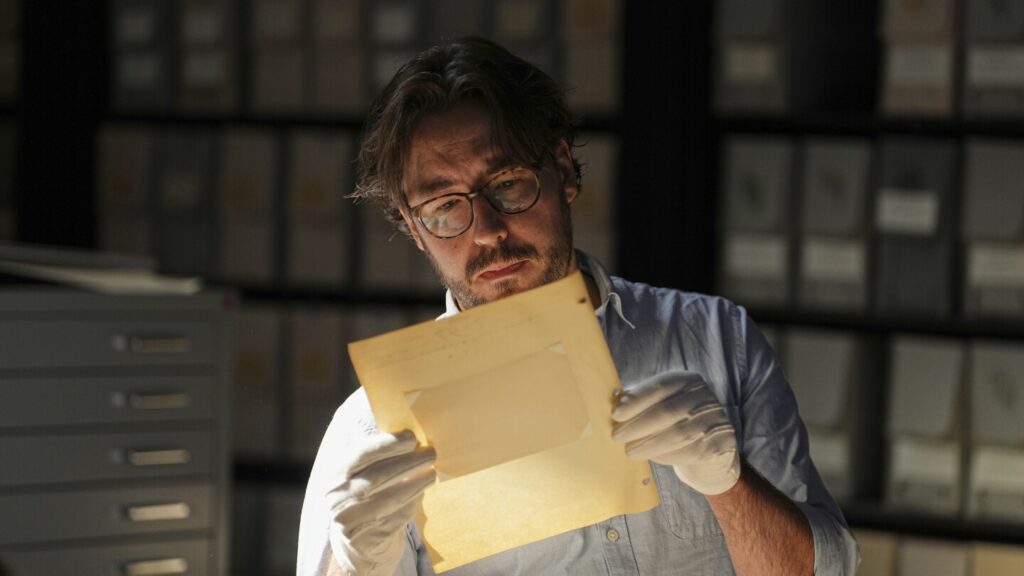

1 photo – Yazidi Shrine – caught the eye of Penn’s doctoral student Mark Marine Webb in 2022. Looting the area. Webb and others began scrutinizing the museum’s files, collecting almost 300 photos and creating a visual archive of the Yazidi people, one of Iraq. The oldest religious minority.

The UN called a systematic attack genocidekilled thousands of Yazidis and sent thousands more. Exile or Sexual Slavery. They also destroyed much of their built heritage and cultural history, and then the small community was division all over the world.

Ansam Basher, now a British teacher, was overwhelmed by emotions when he saw a picture, especially a batch of grandparents’ wedding day in the early 1930s.

“No one would imagine someone of my age losing history due to an ISIS attack,” the 43-year-old said using the acronym for extremist groups. Basher’s grandfather lived with his family while growing up in Basica, the town outside of Mosul. The city fell in 2014.

“My albums, my childhood photos, all the videos, my two brothers’ wedding videos (and) photos have disappeared. And now I’m sure my grandfather and great grandfather suddenly come back to life again. This is what makes me so happy,” she said. “Everyone does.”

Cash of Cultural Memory

archive Document traditions that seek to erase the people, places and traditions of Yazidi. Marine Webb works with Toronto documentary Nathaniel Blunt to share with the community, both through local exhibits and digital forms with the Yazidi Diaspora.

“When they came to Sinjar, they went around and destroyed everything. Religious and Heritage“We’ve seen a lot of experience in our lives,” said Blunt, a postdoctoral student at the University of Victoria Library. Sinjar is the home of Yazidis ancestors near the Syrian border.

The first exhibition took place in the area in April, when Yazidis gathered to celebrate the New Year. Some were held outdoors in the very area where photographs were recorded almost a century ago.

“(It) was perceived as a beautiful way to regain memories, a memory that was directly threatened through the ethnic cleansing campaign,” Marine Webb said.

Basher’s brothers had been visiting their hometown from Germany when they saw the exhibit and recognized their grandparents. It helped researchers fill in some voids.

The wedding photo shows the elaborately dressed bride as she stands worriedly at the door of the house, proceeding on a dowry to her husband’s village, and finally enters his family’s house so that the crowd can be seen.

“I’m watching my sister in black and white,” Basher said. I noticed a similar green eyes and skin tone I share with my sister’s grandmother, Nama Suleiman.

Her grandfather, Bashir Sadiq Rashid Al Rashid al Rashidhani, came from a prominent family and often hosted Penn Archaeological crews in his cafe. He and his brothers, like other local men, worked on excavations and urged Westerners to invite them to his wedding. They took turns taking photos and even rented the couple a car for the opportunity, the family said.

Some of the photos were taken by Ephraim Avigdor Speyser. Ephraim Avigdor Speyser is an archaeologist at the Penn Museum, who led excavations at two ancient Mesopotamian sites in the region, Tepe Gaura and Ter Villa.

“My grandfather was talking a lot about that time,” said Basher, who uses a different spelling of the family’s last name with other relatives.

Her father, Mohsin Bashir Sadiq, 77, is a retired teacher who now lives in Cologne, Germany, and considers it the first time anyone in town has used a car. It can be seen behind the wedding procession.

Basher shares photos on social media to educate people about their hometown.

“The ideas and drawings they think about Iraq are very different from reality,” she said. “We struggle with a lot of things, but we still have some history.”

Photography, history awakened

Other photos from the collection show people at home, at work, and at religious gatherings.

To Marine Webb, an architect from Barcelona, they show Yazidis when they lived, rather than equating them with the violence they endured later. Locals who saw the exhibit told him, “We and the people are showing the world.”

The isolated minority, Yazidis, has been persecuted for centuries. Many Muslims consider them to be pagans. Many Iraqis mistakenly view them as worshippers of Satan. They spoke Kurds, their traditions are fused and borrowed from ancient Persian religions of Christianity, Islam and Zoroastrianism.

Basher is grateful at the museum at this point that he remains safe if the photos are barely visible. Alessandro Pezzati, a senior archivist at the museum, was one of several people who helped Marine Webb with combs through files to identify them.

“Many of these collections sleep until people like him wake up,” Pezzati said.